Army life: the other side of the story

ForcesWatch comment

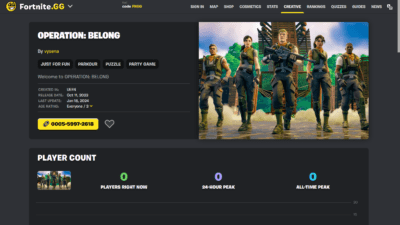

A young boy shivers, the steady rain dripping through his hair and down his mud-streaked face. His eyes are wide and fixed. But then, he’s not alone. Another joins him, also dressed in combats, and pours him a cup of tea from a flask. More come, and he’s surrounded by comrades, sitting silently, checking their rifles. One ruffles the top of the boy’s head affectionately, and he grins.

‘This is belonging’ says the screen. ‘Army: Be the best. Find where you belong, search Army Jobs.’

Another scene follows, with a line of soldiers traipsing up a desolate, snowy mountain slope. The camera zooms in on the line – one trips, and another helps him up. One begins whistling, then sings, ‘I’m having the time of my life.’ ‘You sound like a dying cow,’ jests a comrade in a Scottish accent, and they all chuckle, trudging on together.

‘This is belonging’ says the screen. ‘Army: Be the best. Find where you belong, search Army Jobs.’

Make incredible friends. Embrace adventure. If you want an extraordinary job, join the Army https://t.co/AdPe3hq5cC #FindWhereYouBelong pic.twitter.com/6ZF3M9Gz8r

— Army Jobs (@armyjobs) January 14, 2017

These mini videos form part of a £3m advertising campaign launched by the British Army at the start of 2017, in an appeal to children (any under eighteen year olds by international standards) and young people.

The theme is belonging, a theme also emphasised for recruitment purposes by sports teams, religious groups, gangs, fraternities and sororities, political organisations and other entities in which conformity and distinction are key. It appeals in particular to adolescent children who are undergoing the most intense phase of their process of social identity formation.

All the confusion, instability and changes adolescents face, are compounded by their under-formed personal and social identities, resulting in their tendency to over-identify with others or with groups in order to gain a sense of security and belonging. These might take the form of love interests, cliques, or even gangs or extremists.

By appealing to the adolescent child’s need to belong, the army have therefore latched onto a very popular recruitment tool, powerful in particular among those who feel isolated or marginalised, or who have a sense of non-belonging and potentially low self-esteem.

‘A sense of belonging may sound like a small thing. Yet it fuels you as much as food and water, because it doesn’t just feed your body, it feeds your mind and soul.

The stronger the sense of belonging – the stronger you become.

Sure, you could look for belonging in a football team or a club, but the sense of belonging you’ll find in the Army – well, that’s the next level…’

The promised reward of signing up is ‘belonging’ to the army is becoming stronger and stronger by virtue of ‘belonging’. This is tempting indeed for adolescents who tend to crave social acceptance and a feeling of importance in a group context.

The army also claim to offer a sense of belonging stronger and more powerful than any other: ‘When you’ve trained together side by side, learnt things no classroom can teach you and fought with each other, for each other – that creates a bond like no other. A bond that lasts a lifetime.’

But telling adolescents that they can resolve their need to belong by joining the Army is simplistic and one-sided. The reality is many aspects of army life are potentially harmful, especially to vulnerable individuals. The other side of the story needs to be told.

What are the conditions of belonging in the army?

The erosion of self-determination, of autonomy of movement and of privacy and choice of personal appearance are all integral to the training regime in which recruits are anonymised and controlled. They are subject to relentless activity and the resulting fatigue, to authoritarian power and an absence of civilian norms and social support, which can cause anxiety and disorientation.

In a series of short films for Child Soldiers International released last week, young veteran Wayne Sharrocks speaks of mass punishment, violent abuse, recruits pushed to the point of suicide, and a culture of fear and silence. Bullying and harassment are endemic in the military according to countless reports, and ‘young recruits are at greater risk of bullying, harassment and self-harm than older recruits.’

Sharrocks talks of being conditioned into abandoning your feelings, into becoming robotic – learning to kill, obeying without question, and being part of a ‘tribe mentality’ where you will ‘do whatever they say, whenever they say it, and if you ever question what [they] say [they’re] going to brutally punish you.’

So what of the ‘perks’? The excitement, the adventure, the travelling the world? This is a far cry from the largely boring, mindless daily life in the army that Sharrocks describes. He dismisses the glossy marketing, pointing out that war zones are not the same as Ibiza and that watching your friends get blown up and die is more nightmare than adventure.

What happens to that sense of belonging if you decide to leave the army?

According to the same young veteran, ‘when you leave the army you’re sort of left in this limbo where you’re not in the military so your friends in the military don’t see you as a military guy anymore, but you’re not… you don’t feel like you’re a civilian, so you’re sort of in this limbo state where you don’t feel like you can identify with either or… so you sort of feel very alone, and vulnerable.’

His experience is, sadly, far from unique. Isolation and loneliness are widely known to affect many veterans upon return to civilian life. Many are at risk of depression, self-harm and suicide – and the younger they sign up, the more likely they are to face mental illness later on.

The army says it offers a bond that ‘lasts a lifetime.’

But where was this life-long bond for Sharrocks, who speaks of the isolation faced by those who leave the army – and being rejected by the ‘clique’ to which he once belonged. He says, ‘you leave with no idea of how to engage with people emotionally… friends for life is a load of rubbish.’

If there is any ‘bond like no other’ shared by veterans, for Sharrocks this bond is a little different from the one presented by the army advertisements. He says, ‘I had a meet up with a few friends the other day and there is like a bond there – but you all just moan about how rubbish the army was, that’s what you spend your time thinking of.’

Indeed, fewer than half of army soldiers say they’d recommend army life to a friend. Upon leaving the forces, many veterans struggle to rebuild the social support networks they need, which leaves them more vulnerable to delayed-onset mental health problems.

What if the army is not necessarily the answer to an adolescent child’s need to belong?

Clinical psychologist and co-author of the report The Recruitment of Children into the UK armed forces: A Critique from Health Professionals Sally Zlotowitz has the following advice regarding feelings of isolation, loneliness and the need to belong during this crucial stage of human development:

‘Adolescence is a key phase for connecting with friends and finding your identity, through who you spend time with and what you do together. It’s quite usual for adolescents to be concerned about ‘fitting in’ and being liked by others. Indeed , everyone has these worries! But if an adolescent feels very lonely and isolated, it’s really important that they can be offered or have available a range of ways to connect with others.

It’s also vital for good well-being that young people feel authentically themselves in whichever group they belong to. If young people feel they are mostly ‘hiding’ parts of themselves, unable to express certain emotional experiences and values, or inside don’t agree with some of the group behaviour, then in the longer term this will just make the sense of isolation worse. Having someone you trust outside of the group who you can talk to and reflect on your experiences with, can help with knowing when a group is not actually making you feel good anymore.

The structures of the army might well help some young people to find a sense of belonging. But this must be balanced with knowing the risks, including how difficult re-integration into society can be later down the line, especially if you join under 18.’

With their new marketing campaign, the army lays claim to a certain level of ownership over the human desire to belong. But when young recruits sign up looking to quench this desire, it is important that they are aware of the other, more problematic, sides of army life.

Adolescents must also understand that there are many options and ways in which they can seek help and guidance if they are feeling lonely or isolated. And perhaps it is time that the Ministry of Defence listens to the majority of civilians, to the United Nations, to all four UK Children’s Commissioners and multiple child rights and human rights organisations, all of whom believe that children do not belong in the army.

______________

Before You Sign Up is a website for young people and their parents who are thinking of joining the army, and for soldiers who are thinking of leaving. It provides accurate and balanced information about the army, so that the site’s users can better decide on what’s best for them: http://www.beforeyousignup.info/

See more: recruitment, risks, veterans, advertising, bullying and assault

Like what you read?

> Sign up for our newsletter or blog notifications

> Support our work – from just £2 a month