The inescapable psychological cost of conflict

ForcesWatch comment

A study published in the Lancet called Violent offending by UK military personnel deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan has found that men in the UK armed forces are more likely to have been convicted of violent offences than their civilian peers. The study shows a strong link with age – that fighting and being traumatised by it tends to make those in younger age groups more likely to be violent afterwards.

The study of almost 14,000 servicemen who have been deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan looked at the link between their criminal records and military service. It found that 20% of young males under 30 had a conviction for violent offences compared to 6.7% in the general population. The incidence decreases for older age groups and for higher ranks. Those who had taken part in combat were more than 50% more likely to be involved in post-service violent episodes. The incidence increased with multiple combat occurrences and most significantly, violent behaviour prior to signing up. Alcohol misuse, PTSD and high levels of self-reported aggressive behaviour are all strong indicators of post-service violence.

“Our study, which used official criminal records, found that violent offending was most common among young men from the lower ranks of the Army and was strongly associated with a history of violent offending before joining the military. Serving in a combat role and traumatic experiences on deployment also increased the risk of violent behaviour”, explains Dr Deirdre MacManus from King’s College London, who led the research.

Although ‘overall lifetime offending’ in general is lower in the military than in the whole population, ‘lifetime violent offending’ is more common (11% vs 8.7%).

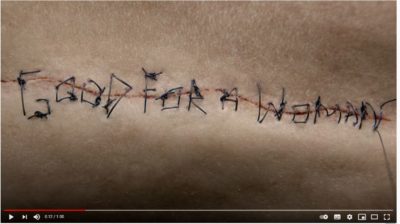

Pre-military history of violence, younger age, and lower rank were the strongest risk factors for violent offending along with exposure to combat. Often repeated trauma experienced in combat situations is one factor but the report also suggests further links between combat and post-service violence – that those in combat roles are taught aggressive responses: “Combat experiences might affect an individual’s propensity to violent behaviour through various mechanisms including preparatory pre-deployment training to instil attitudes that enhance survival and ensure troops are able to commit targeted aggressive acts.”

It also notes the role that selection to combat roles will play: “deployment in a combat role is not a random process. Indeed, individuals who volunteer or are selected for a combat role are likely to have a propensity for risk taking and aggressive behaviour. In the UK, infantry units have traditionally promoted aggression as a desirable trait and such units frequently recruit individuals who are socially disadvantaged and are likely to have low educational attainment.”

A wider perspective

Dr MacManus states that, “The findings provide information that can enable better violence risk assessment in serving and ex-serving military personnel”. However, when a wider perspective is taken, a number of other conclusions can be drawn about how to reduce the likelihood that young service personnel from disadvantaged backgrounds are involved in post-service violence:

- The military should not be presented as the only escape route out of social disadvantage – joining up is often promoted as a means to self-development, a stable job and good career for those with few alternative options. For many, particularly in combat roles such as in the infantry, it gives them few skills for life outside of the military. Instead of the Government seeking to provide a wider array of opportunities for these young people, they are actively promoting ‘military skills and ethos’ as part of their national education policy. Military-led activities are being piloted as an alternative to mainstream educational provision for those at risk of being excluded. Cadet forces are being expanded within state education and ex-service personnel are being promoted as role-models and educators. While funding for these schemes is abundant, money for other youth services are cut. These schemes will channel more vulnerable young people into the military from an earlier age.

- Recruits should be 18 years old before they can enlist – this is inline with recommendations from the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child as well as the UK Parliament’s Joint Committee on Human Rights report on Children’s Rights and would help to ensure that they join up on the basis of informed decisions about what they are getting in to and how it could affect them. Research indicates that infantry recruits tend to be younger and from more disadvantaged backgrounds than those joining most other branches of the armed forces. It is these young infantrymen who are most at risk from fatality and serious injury as well as post-service difficulties.

- A more balanced picture of life in the armed forces should be presented to young people. Those directly responsible for the welfare of young people, those in education, careers advice, and parents have a tough job to create this balance in the face of the media, games and entertainment industries that create a distorted image of the costs of warfare and the interests of politicians and the military itself which portray in unbalanced image of armed forces in order to attract recruits.

The psychological costs of learning to kill

As Lt. Col. Dave Grossman argues in ‘On Killing: The Psychological Cost of Learning to Kill in War and Society’(also see killology.com) the military utilises powerful techniques to overcome the instinct within most soldiers to not kill in battle. The resulting psychological cost for soldiers is devastating. There is also a social cost for the rest of us as we are conditioned into an acceptance of violence.

However much we seek to mitigate the situation with post-combat screening or assistance, we can’t escape the fact that the military, in training its recruits, is conditioning them against social norms and towards the act of killing. We can’t be surprised when such conditioned responses can not be contained or that the involvement in armed conflict often leads to trauma which will have a lasting impact on those involved. The individual soldier has always paid this price to a military that needs and feeds on violent responses to conflict. Without seeking to reduce armed conflict, there is a limit to what the military establishment can do about this situation.

See more: risks, mental health

Like what you read?

> Sign up for our newsletter or blog notifications

> Support our work – from just £2 a month