Militarising the crisis?

The military continues to render aid to civil authorities as part of the Covid Support Force. Early in that process we pulled together a short analysis of what the military were doing, and the Ministry of Defence provide a regularly updated summary of their contribution to the coronavirus response.

More recently however, we have observed that the military seem to be utilising opportunities provided by the crisis for promoting the armed forces and the ‘defence’ sector. At the same time, the crisis has helped create the possibility of a global ceasefire and fast-forwarded debate about what human, rather than state, security actually looks like.

Recruiting opportunities

We are concerned that the military may see the Covid-19 crisis as a chance to recruit. This seems to be happening at a number of levels. For example, the head of the Royal Marines, individual infantry regiments and serving Ministry of Defence ministers have all linked the pandemic with calls for people to join/re-join. The ethical implications of this should be obvious, not least at a time when many people are concerned about their jobs and about a potential recession.

The language of war

It is hard not to notice how the embedding of military language in the political and media vocabulary, which has taken place over the last 20 years of the War on Terror, has also become commonplace in discussion of the crisis. Terms like ‘front line’ and ‘exit strategy’, which clearly have their origins in the military, are in wide use without apparently much consideration of how they arrived in the lexicon.

The Guardian’s Marina Hyde wrote an excellent piece warning about framing the crisis as a war, noting that it is not health and care sector workers using this language. German president Frank-Walter Steinmeier also pointed out the contradictions in this idea, as the pandemic requires an approach which prioritises solidarity and humanity. WW2 historian James Heartfield looked at the disparity between the mythology of that war, including the ‘Blitz Spirit’, and the current health emergency. Cynthia Enloe, writer and teacher on feminism and militarism, reflects that talk of ‘waging a war’ does not help to address the global and local challenges presented by the coronavirus or help us ‘to craft approaches that enhance social justice, gender equity, and sustainable peace’ in the aftermath.

The ceremonial aspects of military culture have also been drawn on. The spitfire and hurricane salute to Captain, now Colonel, Tom Moore on his 100th birthday have developed into a larger one which will also fly over a veteran’s care home and NHS hospital on 8 May to celebrate the 75th anniversary of VE Day and the end of Second World War in Europe.

To fuse the military with the Covid-19 response more fully, the chair of the Defence Select Committee Tobias Ellwood has suggested that the Red Arrows should perform fly-overs of British cities during the Thursday ‘clap for the NHS’ to raise ‘national morale’, as the Air Force and Navy are doing in the US. UK health workers struggling to obtain adequate levels of PPE and putting their lives at risk as a result have not appreciated this calculated and patronising suggestion.

Promotional opportunities

The UK (and global) military establishment appears to be desperate to position itself at the centre of the crisis response. There is no doubt that the contribution of the armed forces has been laudable in parts, with military medics, aircrews and drivers all taking key roles in supporting front line workers, and at some risk to serving personnel. But it is noticeable that the military has recently used media and public statements for messaging that has a promotional dimension. An anonymous military source criticised the NHS’s planning ability in a report in The Times. The article suggests a frustration that the military had not been given a bigger role in the Covid Support Force ‘given that planning and logistics are military specialisms’. This line was taken up the Tobias Ellwood MP who tweeted that ‘the MOD’s command, control & communications, situational awareness and strategic thinking, is not being fully utilised to achieve the mission.’

Then, in an unsettling display of military influence, the Chief of the Defence Staff, General Sir Nick Carter, was given a prominent role in the government’s daily press conference. Leading the briefing, Foreign Secretary Dominic Raab spent some time praising the contribution of the armed forces to the Coronavirus response, stating that troops ‘offer a calm reassurance that the task is at hand and we will come through this crisis’. Apart from this statement being highly contestable, the timing of it suggested that the government were attempting to deflect attention away from issues about their own performance. General Sir Nick Carter then, inappropriately, took the opportunity to make a statement that, even in the face of this new threat, nuclear weapons and controversial overseas missions remain key to national security.

As the Peace Pledge Union have pointed out, to talk of the armed forces still ‘protecting the country’ during the Coronavirus crisis, is an attempt to prioritise military protection over that provided by health workers and others in essential civilian roles. What ‘protection’ and ‘security’ will come to mean in the post-Coronavirus world could become a vigorous public debates, particularly with the forthcoming Integrated Security, Defence and Foreign Policy Review. It is clear that the military are positioning themselves to argue for the primacy of military-based ‘defence’, pushing their own role in providing national ‘resilience’ to the fore, as argued by the Defence Secretary in a recent parliamentary evidence session about the military’s response to Covid-19.

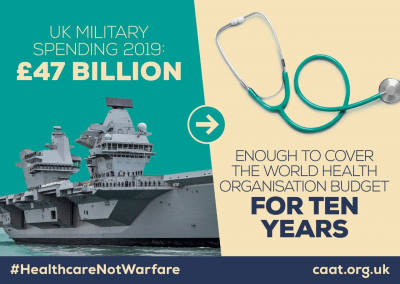

Despite the coronavirus making ‘the world’s mightiest navy pointless’, the former head of the British Army, General Sir Peter Wall, has continued to argue for a 50% increase in defence spending, from 2% to 3% of GDP, in order to keep the UK as a ‘credible player on the world stage’. The postponement of the Review provides a welcome opportunity for a newly framed public debate around how resources should be directed towards the very real threats to human security that people face rather than military vanity projects.

The MoD have also chosen this moment to launch a report on The Utility of Military Force and Public Understanding in Today’s Britain. The report, whose principle author is military historian Professor Sir Hew Strachan, was simplistically presented by the media as an argument for the reintroduction of national service. However, it does engage with some interesting areas of discussion around civil-military relations, although ultimately resting on some unchallenged assumptions and limited critique. We shall explore the report in more depth shortly.

Less nuanced is the Defence Instruction Notice published last week on contact between military personnel and the media. This reiteration of the rules that all communication must be authorised in advance is unlikely to help develop the ‘mature debate’ necessary to bridge the ‘communication gap between the government and the public on matters of defence policy’ that the Strachan report identifies.

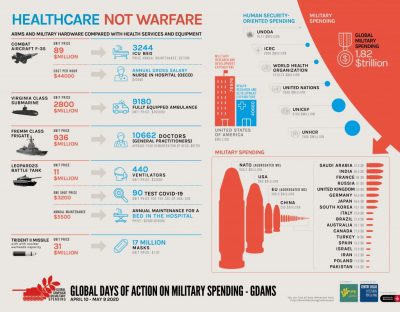

New data released by the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute in April 2020 reveals a post-WW2 record in military spending in 2019. From the Global Campaign on Military Spending.

Challenging defence as usual

In response to the United Nations Secretary General’s call for a worldwide break in armed violence under the banner of a global ceasefire, more than 2 million people and 70 member states around the world have now supported it. Although major powers on the UN Security Council are not enamoured with the idea, the UK Foreign Secretary Dominic Raab has supported it. However, as the Campaign Against Arms Trade makes clear, this needs to be backed up with ceasing to sell weapons as well as ceasing to fire them.

#HealthcareNotWarfare. From the month of action on military spending.

While the pandemic has already seen the UK draw down some troops from long standing deployments like Iraq, it was revealed that the RAF and BAE Systems continue to be active in supporting Saudi Arabia’s assault on Yemen. In evidence to the Defence Committee, the Defence Secretary Ben Wallace said that arms industry production has been encouraged to continue. How support for a global ceasefire becomes more than just gesture politics, explored in this article by The Crisis Group, and how the Covid crisis impacts our collective understanding of security and the role of ‘defence’, will be an important public debate in the coming years.

See more: military in society, recruitment, Covid-19

Like what you read?

> Sign up for our newsletter or blog notifications

> Support our work – from just £2 a month