Do we want militarised schools? Cadet forces, ‘independent’ evaluations and defence agendas in education

Read a PDF version of this report

Summary

In August the government announced £70m of new funding for the UK’s military cadet forces. The pledge to increase the number of cadets by 30%, or over 40,000, by 2030 was made in June’s Strategic Defence Review. The review also stated that a further increase would see cadet numbers rising to 250,000 ‘in the longer term’.

Much of this expansion will be in school-based cadet forces. Since 2012 it has been government policy to increase the number of armed forces cadet units in state-funded secondary schools. To back up the expansion the Ministry of Defence commissioned the University of Northampton to produce a series of evaluation reports to demonstrate the social impact and value of cadet forces.

The first of these reports came out in 2017 and the most recent in April this year, with a report published almost every year in between. The reports have provided the government with a string of similarly highly positive findings and made claims about huge financial benefits to the country. They have been used to generate press releases, media coverage and parliamentary debates, and provided justification for the spending on cadets – estimated to be £210m a year. The narrative around cadet forces is now one of an almost uniquely beneficial response to some of the problems faced by young people and disadvantaged communities.

We investigate how the evaluation research has served the political purpose of those who funded it and how a number of issues relating to independence, framing and methodology raise some of the red flags that the Education Endowment Foundation lists in relation to evaluations of this kind. These concerns undermine the case that cadet forces provide something to young people that other youth provision cannot. And we look at how the research has been used as a political tool to justify the policy over the years.

We outline why this particularly embedded form of military creep into education institutions is problematic: it brings defence agendas into schools and utilises disadvantage as a means to do this, and normalises and politically neutralises the military, reducing the space for debate and diversity of opinion around approaches to conflict. Identifying positive outcomes from cadet forces is not adequate justification for embedding the military into education and pulling young people into its orbit while they are still at school.

Although it is still only a minority of schools that have a cadet force, they have gained popularity as their military function is downplayed and narratives around educational and social mobility benefits have been promoted. Yet, this risks being undermined by current defence debates in which the role that cadet forces play in fulfilling the needs of the armed forces – as ambassadors for defence and as future recruits – is made more explicit. That the fundamental purpose of cadets units in schools is to forward a defence agenda is something that schools should consider very critically.

Contents

- ‘Military ethos in schools’

- Enter the University of Northampton

- Research framing issues

- Methodological issues

- Very positive conclusions, unsurprisingly

- The political capital of cadet evaluations

- Cadets in the ‘war-footing’ era

- Militarised schooling – in whose best interests?

- Read a PDF version of this report

‘Military ethos in schools’

In 2012 the Coalition government announced a number of policies under the umbrella of ‘military ethos in schools’. Although the presence of the armed forces in schools, through visits and cadet activities, was already established, a formal partnership between the Department for Education (DfE) with the Ministry of Defence (MoD) was a new development. The context for this was the perception that the armed forces required more visibility and ‘recognition’ after the Iraq and Afghanistan wars, as well as the ever-present need to get recruiting messages to young people. The ideological tendency towards traditional values of those in charge of the DfE was also palpable. ‘Military ethos’ was one of a number of education policy fads relating to character and resilience, and was presented in a purely positive light as a kind of proxy for ‘British values’ which also became prominent in education narratives at that time. This moralistic tone continues to echo with the minister of the current government suggesting that ‘cadet training could give young people growing up “with perhaps slightly looser boundaries” better discipline and principles in preparation for adult life’.

The Cadet Expansion Programme has been the most successful element of the ‘military ethos’ initiatives, although the policy also helped establish a number of private companies staffed by veterans (such as the MPCT described below) who provide military-themed activities in schools. By the start of 2020, the government were able to announce there they had reached their goal of 500 in-school cadet units. These currently serve around 50,000 cadets. There are another 88,000 young people in community units – Sea Cadets, Army Cadets, Air Cadets and Volunteer Cadet Corps – which run outside of schools.

Enter the University of Northampton

In 2016 a four-year research project was commissioned by the MoD, the Combined Cadet Force Association (CCFA) and the Cadet Vocational Qualifications Organisation (CVQO) to explore ‘What is the social impact and return on investment resulting from expenditure in the Cadet Forces in the UK?’ The CCFA oversees the Combined Cadet Force – which are the units located in schools – and the CVQA oversees qualifications that cadets, and the adult volunteers who work with them, can gain.

Since 2017 the ISII has published at least eight reports on the cadet forces.

The work was carried out by the Institute for Social Innovation and Impact (ISII) at the University of Northampton and led by Professor Simon Denny. Following a career in the British Army in the 1970s and 80s, Simon Denny worked in higher education on training and enterprise projects and became Professor of Entrepreneurship at the University of Northampton. He set up the ISII in 2010 but has worked as an external associate since 2018.

In 2019 Denny became a trustee of CVQO, which now operates under the name of the Cadet Vocational College, one of the bodies that was commissioning him to conduct the research. As well as receiving annual government funding for its education work, CVQO was also awarded a grant of £750,000 under the DfE’s ‘military ethos’ programme in 2013 and a LIBOR-funded grant was awarded in 2016.

Since 2017 the ISII has published at least eight reports on the cadet forces including three interim reports and a final report for the four-year study, two reports on the value of cadet forces to Wales and a similar report for Scotland. Another report was published this year about the value of cadets in schools and was based on additional research conducted after the four-year study.

It also appears that a ninth report was published in 2023 on The Impact and Value of School-Base Cadet Force Detachments in the UK, but this does not seem to be available online. This suggests that the 2025 report, which has an almost identical name, could be a repackaging of the 2023 report, particularly as the research in the 2025 report is from 2023.

The ISII also put its name on two reports authored by Simon Denny on the impact and value of cadet qualifications for CVQO in 2021 and 2023, after he became a trustee of the organisation.

In addition to all these reports about cadets, the ISII published three reports about the Motivational Preparation College Training or MPCT, which runs around 30 military academies around the UK, providing training for young people aged from 16 years who are interested in joining the armed forces. It also provides military activities for schools.

Research framing issues

The remit of ISII’s research has been to ‘help understand the social impact and return on investment resulting from the MOD’s expenditure on cadets and the Cadet Expansion Programme, as well as the benefits of the qualifications provided by CVQO’. When the first two interim reports were published in 2017 and 2018, we wrote (here and here) of our concerns about the purpose and framing of the research, which seemed almost set up to provide a positive evaluation of cadet forces and the government’s already committed investment. We have now also looked at concerns with the methodology of the most recent report, and how the research and its conclusions have been used politically as the succession of reports have been published over the years.

The narrow and uncritical framing affects the design of the research, most importantly its failure to compare outcomes with the impact and value that other youth organisations also have.

The framing of ISII’s research has directly adopted some of the government’s political language. The first ISII report quotes the then Prime Minister on social mobility as giving ‘ordinary, working class people …. the chance to go as far as their talents will take them’. The final report references the defence narrative that cadet forces are a wider service to society, ‘to help promote UK prosperity and civil society’. This less-than-neutral framing seems to overly reflect the interests of the organisations who have commissioned the reports, starting with an assumption that cadets are beneficial, with the task being to establish by how much. The narrow and uncritical framing affects the design of the research, most importantly its failure to compare outcomes with the impact and value that other youth organisations also have.

The reports take for granted that encouraging children via what is packaged as a ‘youth organisation’ towards a career in the armed forces is a good thing, and do not explore evidence which suggests that military service can be damaging particularly to very young recruits and particularly to those from disadvantaged backgrounds. This is despite the explicit targetting of the Cadet Expansion Programme towards more disadvantaged communities. On the contrary, some of the reports make recommendations for more resources to be allocated to allow for more young people to become cadets.

But what is in the best interests of young people is only one part of the story. The researchers engage with the armed forces, veterans, various government departments, cadet associations, adult volunteers in cadet units, and others, to try to determine how the cadets create value for numerous stakeholders. It puts figures on the benefits to government departments and society as a whole (while stressing that the costings are only ‘indicative’). This financialised approach reflects a perception that youth work must be measurably beneficial to the wider community, creating a prescriptive view of how young people can serve society. A critique of the ‘social investment machine’ in UK youth work is made by Tania de St Croix et al, who explore how this approach, with its ’emphasis on particular social outcomes and value’ also becomes ‘a means for the government to pursue a broader political-economic and socio-cultural agenda promoting neoliberal aspiration, personal responsibility and individualised notions of social mobility’.

Methodological issues

This year’s ISII report is based on additional research with a narrower focus than the four-year project. It explores the benefits to cadets based in schools and to the schools which run cadet units. In addition to the framing issues identified above, the research design and methodology flags up a number of concerns around bias and sample size, lack of comparable data from non-cadet groups, and lack of control for other factors. Some of these concerns also apply to the four-year study although that research captured data from many more people.

The latest evaluation uses qualitative and quantitative data collection methods across a range of stakeholders. The qualitative data seems to be skewed away from the experience of schools and cadets themselves. There were only seven interviews conducted with cadet staff in schools and only nine headteacher or senior leadership interviews. Over 70% of the 54 interviews were with people elsewhere, mainly in government departments and cadet associations, and with senior military officers; this last group were interviewed most. No cadets or their parents were interviewed at all.

These issues suggest a significant possibility that bias was introduced by the small and unrepresentative sample, and the selection – or self-selection – of adults and young people in schools who are likely to be the most enthusiastic about their involvement.

Another 36 headteachers did complete the quantitative survey but only 13 were from mainstream state schools as opposed to independent or grammar schools. Twice as many cadet staff in schools responded, as the survey was distributed via them, while too few school governors responded to be analysed. It is unclear how many surveys were sent out to cadets but only 159 were returned which is a vanishingly small fraction of the 50,000 cadets in schools. Of these, over 90% of the cadets responding were from independent or grammar schools with only 14 responses from mainstream state schools, despite these schools being where the expansion of cadet forces has been targetted. This is a severe shortcoming as the whole experience of being in a cadet unit in a well-resourced independent or grammar school is likely to be very different. Again, parents do not seem to have been surveyed.

These issues suggest a significant possibility that bias was introduced by the small and unrepresentative sample, and the selection – or self-selection – of adults and young people in schools who are likely to be the most enthusiastic about their involvement. This is aggravated by the use of surveys that rely on self-reporting in relation to subjective perceptions, and often in hindsight. Skewing research towards the experience of stakeholders outside of schools and those in independent and grammar schools is also likely to create overly positive results. The researchers mention the use of ‘triangulation of data to ensure the results are valid and reliable’ and having ‘cross-checked the emergent themes with existing literature and other data sources’ to minimise subjectivity bias. They could be referring to their own previous research, but no further detail is given.

Furthermore, and as a ‘limitation’ that the authors themselves acknowledge, the research does not test how the experience of cadets differs from those involved in other extracurricular activities, or how schools with cadet units fare against schools without. This lack of comparative analysis has been a problem across all the ISII’s cadet research. One part of the four-year survey did look at a comparable group of young people not involved in the cadets. Unsurprisingly, this indicates a favourable impact for the cadets but does nothing to show if this value is unique or if strong investment in other youth provision would create similar results.

Very positive conclusions, unsurprisingly

All the ISII reports describe similarly highly positive results for a range of outcomes – including enrichment, attendance, a sense of belonging, opportunities, confidence, well-being, and resilience – and there are no less than positive or cautious viewpoints expressed in any of the work. However, there is also something rather obvious about these findings, as the link between well-funded, structured adventurous activities and building confidence and soft skills is observable across wider youth provision. There are research reports which show that uniformed activities and youth services in general – including youth work taking place in schools – are beneficial in similar ways.

In failing to compare the impact of cadets to other youth provision or extracurricular activities in schools, this work is able to attribute all perceived benefits to something special about the cadets. Another study about the cadets conducted by the DfE in 2018, drew similar conclusions about benefits to behaviour (rather than attainment) but provided more caution in interpreting cadet participation as the single influencing factor, particularly as many cadets also take part in other activities. The study found that, ‘At a more general level, cadets are not that dissimilar in their engagement in school and attitudes towards school than a matched comparison group.’

The positive benefits of cadet units in schools are aided by the established network of organisations behind them, and their status in some schools as ‘mini-departments’ rather than just another activity. While there are likely to be particular characteristics of a cadet force which benefit some young people, such as its highly structured approach, without comparative research this has not been examined beyond anecdotes. That regimented and military-themed activities will not appeal to many in any one school has also not been explored.

While the work advocates for more of this military-centred ‘opportunity’, it fails to acknowledge the wider socio-economic impact of concurrent political decision-making which led to a decade or more of austerity and the decimation of provision for young people.

The University of Northampton also created ‘indicative’ financial estimates of the economic benefits that cadet units could yield. The 2025 report frames these calculations as savings per year rather than the aggregated ‘lifetime benefits’ from the four-year study. For example, referring to a ‘belief’ that being a cadet leads to higher educational attainment (although a direct link has not been established), the researchers use the Unit Cost Database to make a calculation based on the lifetime economic benefit of a one-grade improvement in GCSE results for half of examined cadets in any one year. They state that, ‘the potential economic benefit is circa £56 million, per annum’. Our sense is that this is a flawed way of looking at things as well as a highly speculative exercise, especially without a comparative analysis.

Overall, these evaluations of impact and social value are isolated from the context in which the cadet forces operate. Where the researchers mention poverty and disadvantage, mental health issues faced by young people and the lack of other youth services, it is to suggest how cadet forces can step into the gap. While the work advocates for more of this military-centred ‘opportunity’, it fails to acknowledge the wider socio-economic impact of concurrent political decision-making which led to a decade or more of austerity and the decimation of provision for young people.

The political capital of cadet evaluations

Despite the success of the Cadet Expansion Programme in meeting its targets, there has clearly been a continual need to sell the policy to schools. In 2019 Schools Week reported criticism about a lack of buy-in from headteachers because of ‘fears cadet units were used as a recruitment tool for the armed forces’. Social impact research has formed a not unsubstantial part of the promotion put in place to create buy-in, along with a package of funding and resources and a number of headteacher conferences, where the ISII research was presented.

When the ‘military ethos’ policy was introduced back in 2012 similar research on the societal impact of cadet forces had already been conducted for the Council for Reserve Forces’ and Cadets’ Associations in 2010. The major new study commissioned from ISII in 2016 would justify, in terms of financial as well as behavioural and educational benefits, the influx of funding for the expansion of cadets and the other resources required, as outlined in the Cadet Force Strategy in 2015. This would help create the further change in the perception of cadet units by school leaders that was necessary in order to make it successful. The publication of multiple evaluation reports by ISII has provided many opportunities for government press releases (we counted eight mentioning the University of Northampton research since 2017), even though they have all provided very similar glowing conclusions.

One problem with ‘what works’ language is that it tends to imply certainty around causality or impact.

The lead researcher Simon Denny and other ISII researchers have also spoken at events to advocate for the cadet expansion policy. They presented at the headteachers conferences and cross-party groups on cadets in the Welsh government and the UK Parliament, where their joint presentation with the MoD enthused that, ‘The Cadet Forces are a superb investment for the taxpayer’. Denny is one of ‘a wide range of existing cadet advocates’ that the current government’s Minister for Veterans and People has met with to discuss ‘how to work together to best advocate for our cadets’.

In his introduction to The Politics of Evidence, Justin Parkhurst explores how evidence gathering is never politically neutral. He identifies that one problem with ‘what works’ language is that it tends to imply certainty around causality or impact. This tendency was illustrated clearly when, after just one year of the four-year research project, Denny was quoted as stating that there is ‘overwhelmingly positive’ evidence that cadet forces ‘make a huge difference to improve school attendance, develop confidence and help young people become more successful’.

Even when attributing impact is handled with care in the text of a report, this can then get lost as the headline conclusions erase caution around making causal claims. Messages can be further simplified as the research is re-presented by stakeholders or supporters within political arenas, and any caution as to how results should be interpreted is more or less invisible. Benefits that could be solely attributed to participation in cadet units are definitively described as ‘increasing social mobility’ for those who participate in them. Whether this is of universal benefit or only helps some young people, or whether potential impacts actually play out in practice, are fine details.

In the government’s press release for last year’s report on cadet forces in Wales, which emphasised the ‘edge’ that being a cadet may bring, Denny calls for more children in Wales to join and for more investment in cadet qualifications. There is no mention that he is a trustee of the organisation that oversees these qualifications. He goes on to eulogise about the importance of the cadet forces ‘to the nation of Wales’, stating that, ‘It is vital that the contribution of the cadet forces to Wales is clearly articulated and understood by policy-makers, educational leaders, and employers.’

A similar press release for the 2025 report continued the ‘edging ahead’ theme with the minister describing the cadets as ‘a transformative experience’. Despite the framing and methodological issues (particularly the bias towards independent schools) he states that ‘young people who join the cadets do better at school’ and that, ‘This new report unequivocally demonstrates that being a cadet gives pupils an “edge” in applications for college, university, apprenticeships and employment.’ And despite the only ‘indicative’ financial calculations made by the researchers, the minister states confidently that, ‘In terms of health and wellbeing alone, participation in the Cadet Force produce an annual return on investment in the region of about £120 million each year.’

These conclusions are then mentioned in the media (such as here), and research briefings and are utilised by parliamentarians (such as here and here) keen to draw on the conclusions of the research to express their support for cadet forces in schools.

Cadets in the ‘war-footing’ era

Given the value of cadet forces to the military it was inevitable that they would play a role in the summer’s Strategic Defence Review. As part of a package of ways in which the ‘whole of society’ will play a role, the review pledged to expand the number of cadets by 30% by 2030, and to 250,000 in the long-term. It also mentioned that a two-year series of public outreach events across the UK will take place with the help of reserve and cadet forces. More widely, it was announced that the MoD will work with the DfE ‘to develop understanding of the Armed Forces among young people in schools’ although there are already many of these kinds of activities taking place. There are no details yet about what the ‘national conversation’ will entail but more has been announced about cadet force expansion, including the allocation of £70m of new funding.

An interesting effect of the new ‘war-footing’ context for further cadet expansion is that it acknowledges more openly the link between military activities in schools and the recruitment agenda that drives them.

The defence review also recommended a ‘greater focus’ on cadets learning STEM (science, technology, engineering, mathematics) skills and that, ‘Defence, wider Government, and partnerships with the private sector must provide appropriate leadership, support, and funding to deliver this expansion.’ The minister chose to make the recent funding announcement during a visit to the National Air & Space Cadet Camp’s ‘industry day’ which connected ‘young people directly with over 60 leading companies, turning inspiration into real employment pathways’. Needless to say, some of the largest defence companies in the UK were present and may also become the source of the new private sector funding for cadets mentioned in the defence review.

‘Previous attendees’ for industry day at the National Air & Space Camp.

An interesting impact of the new ‘war-footing’ context for further cadet expansion is that it acknowledges more openly the link between military activities in schools and the recruitment agenda that drives them. The emphasis on the cadet forces as youth organisations with no recruitment remit is less convincing in this new light. The extra resources for cadet forces will include drone training, a National Cadet Champion, and more support from the Regular and Reserve parts of the armed forces. If these were not ‘Defence’ priorities, they would not be happening. Cadets are also viewed as an important conduit for the closer ties between the military and civil society that the defence review envisages; the minister reportedly noted in July at a meeting of the All-Party Parliamentary Group for Reserves and Cadets that,’Cadets result in 200K families having a connection to Defence at any one time.’

Last year the DfE cut its annual grant of £1m to support in-school cadets due to budget pressures. The new report, and the defence review, have provided new opportunities to counter further such moves and to bolster the case for cadets once again.

As an education commentator has noted, the ambition for up to a quarter of a million cadets in state schools could see 7% or more of secondary school pupils enrolled, with huge implications for schools which are already significantly under-resourced. The University of Northampton’s 2025 report discusses some of the pressures that schools face with a fear that expenditure on cadet units may be reduced as a result. Last year the DfE cut its annual grant of £1m to support in-school cadets due to budget pressures. The new report, and the defence review, have provided new opportunities to counter further such moves and to bolster the case for cadets once again.

Militarised schooling – in whose best interests?

‘One “invests” in youth and this means there is an expected dividend.’ Brian Belton 2017

In this exploration of what could be called the politics of cadet expansion and the research commissioned to support it, we are not suggesting that the benefits to individuals of being in the cadets are illusionary. As we have noted, research around participation in youth activities shows similar benefits across well funded activities. But we contend that this is not adequate justification for embedding the military into schools, with their captive audience of possibly impressionable young people. We question whether cadet forces in schools are in the best interests of young people and what other harms could result from this policy.

Bringing defence agendas – and recruiting – into schools

The Ministry of Defence have long understood how ‘engagement’ activities in education benefit the armed forces, through fulfilling the twin defence agendas of promoting recruitment and creating a widespread positive awareness of the armed forces. It has also understood the sensitivities around activities in schools that can be interpreted as recruitment, as this policy and regulations document discusses (section 1.8). This document makes clear the recruitment value of cadets, stating that around 20% of armed forces personnel have been in cadet forces and these ex-cadets are ‘less likely to drop out of initial training, which ultimately saves money for that Service’.

Despite being packaged as youth organisations with social and social mobility benefits, cadet forces – and all armed forces activities in schools and communities – are fundamentally about recruitment.

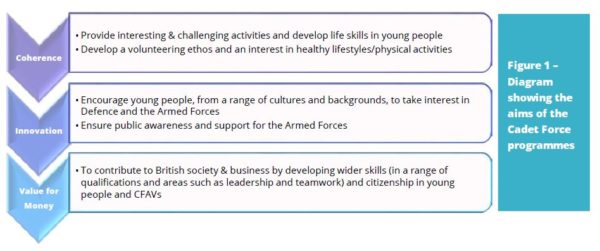

The Youth Engagement Review of 2011 argued that cadet forces have the advantage of fulfilling an additional student development aim which is shared across government departments. Developing this shared interest has helped to deliver the Cadet Expansion Programme. The University of Northampton described the aims of cadet forces in schools as ‘multifaceted’ (see image) which is reflected in the diversity of stakeholders they identified, with many of these from other parts of the military. As well as being targets for ‘soft’ recruitment themselves, young cadets are tasked with promoting and fulfilling defence agendas including the broad remit to ‘engage with local community and employers on behalf of defence’.

From What is the social impact resulting from the expenditure on cadets? An Interim Report, The Institute for Social Innovation & Impact, The University of Northampton, 2017.

Despite being packaged as youth organisations with social and social mobility benefits, cadet forces – and all armed forces activities in schools and communities – are fundamentally about recruitment. The continual political debate about the ‘recruitment crisis’ and how to interest more young people in enlisting, and the role that cadets are given in the Strategic Defence Review, makes this abundantly clear. One of the recommendations of the 2023 independent review on increasing recruitment and retention is also refreshingly honest about the military’s strategies for ‘gaining access to wider pools of willing talent’:

‘Exploit real-life opportunities through current networks. Influencing young people in their early to mid teens is critical. We have heard how recent expansions of cadet forces in deprived areas has had tangible effect, and how visits to schools inspired current personnel. These efforts must continue, and there are opportunities for coordination, for example in sharing excellent British Army material we have seen. There may be opportunities to associate the Armed Forces with opportunities to use specific skills – e.g. supporting college STEM events. Work with the education sector and industry to collaborate on building training and placement pathways in sought after specialisms (e.g. T-Levels). Revisit and promote the routine wearing of uniform in public for serving personnel.’

Utilising disadvantage

The promotion of cadets forces in schools reflects a type of policy making that focuses on individual achievement and routes out of disadvantage for some, rather than reducing childhood adversity and increasing opportunity for all. The social mobility and self-fulfilment narratives are similar to those employed by the armed forces for recruitment marketing. The foregrounding of these individual development narratives takes focus away from ethical questions, such as should inherently violent military approaches be platformed in schools. This approach also utilises the lack of resources and growing inequality faced by many, some of which is a direct result of policy decisions which have cut services for young people and communities over the same time period. The devastating decline of youth services since 2010 has been characterised by the stripping back of general provision and replacement with fragmented services involving a political agenda, such as the National Citizen Service, which the Labour government ended this year. A similar trajectory can be mapped in education over the same period with politically-motivated fragmentation of the school system, underfunding and reduced resources for extra-curricular and student support services. Cadet expansion has partly been justified against the backdrop of these cuts, on the basis that opportunities and resources are particularly lacking in some communities.

With a narrative of social value now attached to cadet forces, the government is able to present them as a social policy response to disadvantage, as illustrated recently by the Minister for Veterans and People:

‘We wish to grow Cadets in areas where the need is greatest. The MOD and the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government (MHCLG) are working together to achieve this aim. In addition to our ’30 by 30’ campaign, MOD future growth plans will be aligned with areas with the highest deprivation levels and the weakest social infrastructure, including MHCLG’s Plan for Neighbourhoods programme places.’

Beyond the hypocrisy and opportunism, focusing cadet expansion on disadvantaged areas risks creating a two-tier system of youth provision based on geography and socio-economic factors. Suggesting that ‘cadets who come from poor homes are able to transform their life-chances’ glosses over how these young people are more likely to be limited to a regimented offer, with its demands for service, and which makes them more likely to end up enlisting in the armed forces. Additionally, and as we have discussed elsewhere, the link between military enlistment and social mobility is problematic and unproven, but there is evidence that childhood adversity can exacerbate negative experiences within the military.

Normalising the military

There is little discussion in any of the cadet evaluations and the political debate about whether the military’s modus operandi of state violence as a political solution to conflict is a suitable context for youth work. The focus on soft skills and behavioural benefits creates an impression that the armed forces are benign institutions and outside of political considerations, with the MoD’s provision of cadet forces as a kind of welfare system for young people. Glossing over its core defence purpose is particularly problematic when the military – with its own institutional authority – ‘engages’ with children and teenagers within the authoritative environment of a school.

How are legitimate and diverse opinions in relation to the military, and objections to military violence on the grounds of conscience, to be taken into account?

Is the presence of militarism in schools conducive to the education of young people generally, and specifically around issues of peace, the non-military resolution of conflict, and human rights? Against the backdrop of global conflict, there needs to be mor, rather than less, teaching around these issues. There is a requirement for teachers to create balance around ‘partisan political views’ – where more than one reasonable perspective may be held – as this Quaker booklet about addressing military engagement in schools discusses. However, the presence of a cadet unit is unlikely to be viewed as a controversial subject requiring balanced debate in a school that hosts one.

While the military and its actions are controversial, and generate widespread political and public debate, the defence review’s narrative of ‘unity of effort’ around an expanded ‘Defence’ sector seems to ignore the capacity it has to create division. Many do not want the military in their schools and the presence of camo in the classroom. How are legitimate and diverse opinions in relation to the military, and objections to military violence on the grounds of conscience, to be taken into account? What about sensitivity to the experience of those in our communities who have been come from conflict situations? It is disturbing to see a call for a cadet force in every school in the name of ‘fixing’ Britain, based on the ISII research and polling, which is similarly blind to these issues. We hope schools assess the evidence with caution, and with an awareness of the politics, to make their own informed judgement.

See more: cadets, military in schools/colleges, recruitment, education

Like what you read?

> Sign up for our newsletter or blog notifications

> Support our work – from just £2 a month