The MPs and the arms company reps

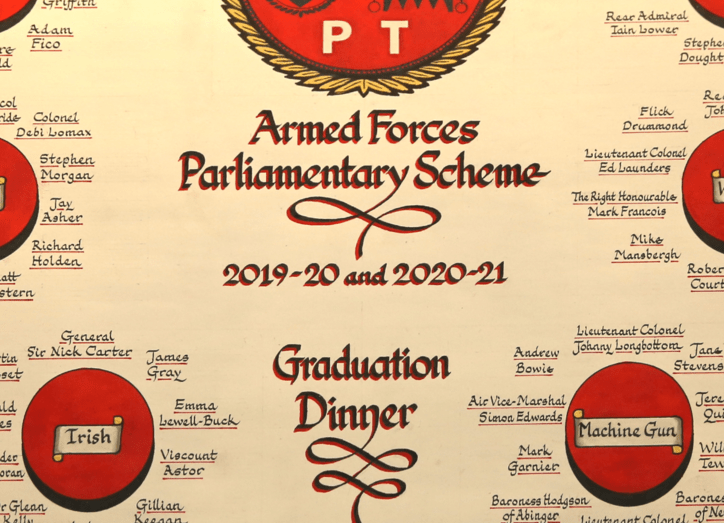

In November 2021 ForcesWatch released its first investigation into the Armed Forces Parliamentary Scheme (AFPS), an annual ‘course’ that purports to educate MPs and Peers about the daily experience of service personnel. To do so, the AFPS puts parliamentarians in uniform and lets them get tactile with tanks, helicopters and automatic weapons. It is as if MPs live vicariously through the Scheme, which presents a kind of martial optics for them to burnish their militarist credentials.

The Conservatives have traditionally enjoyed organic connections to the military and have always been well represented on the AFPS, but an ever increasing number of Labour MPs are taking part. Although this trend began long before Keir Starmer became leader of the party – and started appealing to the patriotism he believes is key to winning back the Red Wall – our analysis shows that many recent participants are on the Labour front bench.

This has a number of implications. Firstly, the Scheme further normalises close connections with – and a favourable ‘understanding’ of – the military as a prerequisite for elected officials. Secondly, with Labour high in the polls, there is a real chance that key brief holders in the next government will have been exposed to military and arms industry influence.… Read more