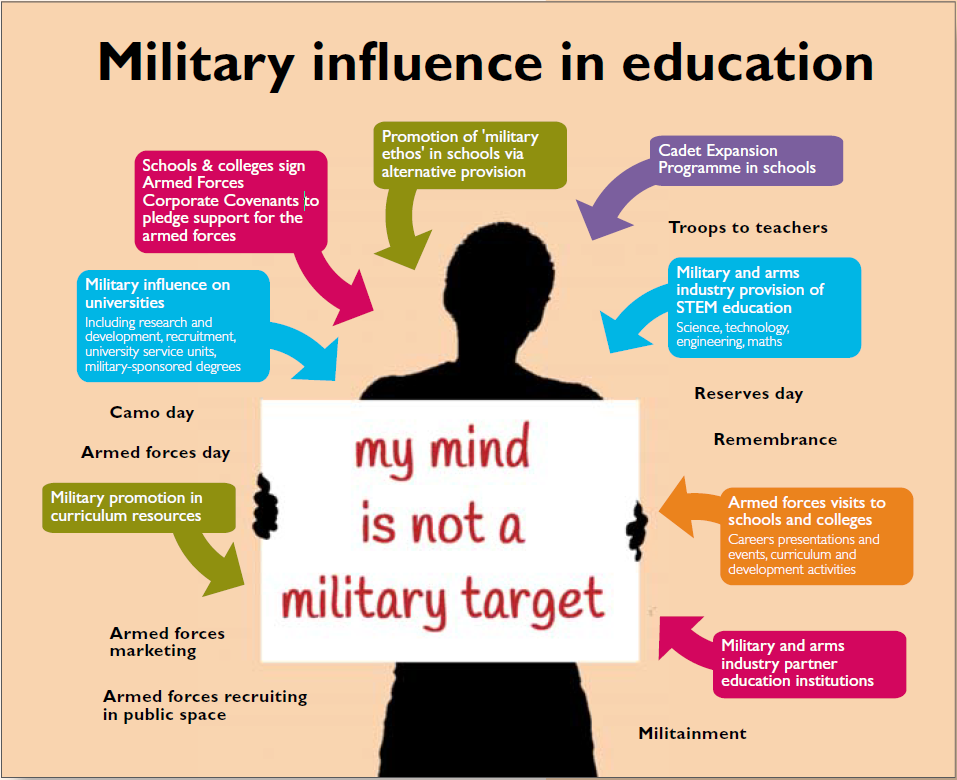

If you want to build public support for the military it makes sense to start young. The education system provides the armed forces with a captive audience for activities related to recruitment and for developing future public support.

Armed forces activity in schools and colleges takes many forms and is on the increase. There are thousands of military visits to schools for presentations and careers events. The armed forces run personal development activities and offer courses providing a taste of military life.

The Department of Education’s policy of promoting ‘military ethos’ has seen the expansion of cadet units in state schools and the provision of military-themed activities by private organisations. This is focused on deprived areas or young people who are not achieving well.

The curriculum provides opportunities for armed forces involvement, such as supporting teaching around the World War I and school trips to battlefields. The current focus on technical and careers education means that the provision of STEM (science, technology, engineering and maths) activities by the armed forces and arms industry has gone unchallenged. The government has also sought to directly promote the UK armed forces and military involvement overseas with The British Armed Forces Learning Resource.

The changing structure of the education system also provides openings for the military. For example, many University Technical Colleges, a new type of employment-focused free school for 14- to 18-year-olds, are sponsored or partnered by the armed forces and arms companies.

Military activities are often presented as character-building, as the solution to poor discipline and attainment, or as a source of skill and knowledge development. The military also has considerable influence in higher education through its recruitment, marketing, research and teaching activities, and university service units.

What is the problem?

The military is involved in schools to fulfil a defence agenda rather than an educational one, yet this has received little scrutiny. Military presentations in schools give a one-sided picture of life in the armed forces and the realities of war.

The armed forces can also direct more resources at education than most other employers, including uniformed services like paramedics or police. Military activities are not necessarily compatible with school policies on equality, tolerance compassion and respect. Not all aspects of ‘military ethos’ are positive and the hierarchy and obedience can be a source of bullying.

The classroom should not be a place for uncritical propaganda or bias. It should be a space for development of critical awareness about human rights, different approaches to conflict resolution and long-term peace and security. Education for, and about, peace is not being promoted by the government, despite recommendations from the United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child (‘Concluding observations’, October 2008, section 67(f)).

Military activities in schools are often targeted at young people whose options are more limited. The best interests of all students must be considered by schools.

Although activities such as military cadets provide positive experiences for many, they do so within a narrow military framework. Given the limited funding in education, expansion could come at the expense of more universal provision, accessible to all students regardless of their interest in military activities. There are many moral questions raised by military activities in schools, so participation should questioned and not assumed. There should be consultation, prior notification and the opportunity to question and even stand aside from a particular activity.