Our curious love affair with the military

The Guardian

Have you detected a growing enthusiasm for all things military? This week the troops were called in to save the Olympics, they’re constantly on our TV screens, and our parks are full of bootcamp fitness sessions for puffed civilians.

Have you detected a growing enthusiasm for all things military? This week the troops were called in to save the Olympics, they’re constantly on our TV screens, and our parks are full of bootcamp fitness sessions for puffed civilians.

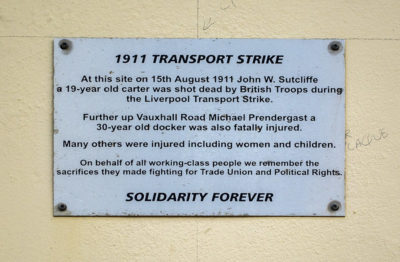

Last week, the MoD admitted that budget cuts would result in fewer boots on the ground, but failed to mention the impact on the documentary makers and TV producers who depend on a ready pool of military “talent”. The cultural industry has done very well out of our recent preoccupation with conflict. The public appetite for war stories means guaranteed top billing for shows with military subjects and kudos for the brave soldiers in front of the cameras. No one seems to have noticed how similar these unflinching portrayals of the harsh realities of military life are, but the accolades keep coming. Six of the 18 documentary entries to the Royal Television Society awards this year were about soldiers. Names such as Harry’s Arctic Heroes suggest they tended to be glorifying rather than analytical. Even the ostensibly gritty ones had stirring soundtracks and a subtext of noble glory.

The military mood music has been playing in the background for while – an insistent tolling that occasionally breaks through all the jubalympic jazz. You could hear it this week when Tony Blair said he was planning to return to public life, and again during the Globe theatre’s recent revival of Henry V. There are dark portents everywhere, and people are panicking. The military build-up in our culture has prompted a large section of the public to put itself on a war footing, with unintentionally comical results. In my locale, high-end housewives are learning the art of making do and mend, while their husbands are squishing themselves into unflattering fatigues on Hampstead Heath for British Military Fitness sessions.

Watching Channel 5’s Royal Marines: Mission Afghanistan recently, I wasn’t inspired to emulate the derring-do of the men on screen, but many viewers are. The civilians signing up for the popular military training courses think they’ll return from costly sorties in local parks pluckier, more determined and better able to cope in their hostile domestic and professional environments. The yompers on the heath look like they have bought into their military personae to varying degrees. I feel sorry for them, but can’t empathise because I’ve never fantasised about being given a dressing-down by someone paid to pretend to be offended by my push-up technique.

Many politicians nurture military fantasies – perhaps they dream of dodging IEDs in Helmand while waiting for their turn at the dispatch box. Labour’s defence secretary Jim Murphy talks about the “unsurpassed contribution” of the armed forces to our national life. The mission statement of the organisation he helped establish, Labour Friends of the Forces, lovingly recalls the contribution of ex-service people like Jim Callaghan who are a “proud part of our history” and promotes the military perspective, lest it be marginalised.

It continues: “We know that there is a wisdom that comes with service that is precious, and it must be an important part of our politics, providing insight and experience to shape important decisions.” Like the Hampstead yompers, it seems Murphy believes the military man will always have the edge over his civilian competitor. Theresa May this week had to call in the army to beef up Olympic security following concerns about the civvy company’s competence, but why stop there? I can picture Murphy and friends in super-clean vests and combats, happily heading up a military takeover of the House of Commons. Dissenting liberals would be forced to do push-ups on Parliament Square while Murphy penned a triumphant Labour Friends of the Forces post, outlining the benefits of beefing up the legislature. As a pragmatist in the mould of Rommel, he’d be certain that decisive authoritarians would make a better fist of the current crisis than equivocating democrats.

A couple of weeks before Armed Forces Day, Murphy urged Labour party members to take the time to say a personal thank-you to a member of the armed forces. Anyone watching the 10 O’Clock News on 30 June would have assumed that Armed Forces Day was an established national fixture, like Remembrance Sunday. You would never have guessed from the newsreader’s sonorous descriptions of fly-pasts in front of predictable dignitaries on Plymouth Hoe that this ritual was instituted by the MoD in 2009, following a campaign by the Daily Telegraph.

In this climate, Stephen Twigg’s suggestion this week that Labour, when it comes to office, should institute military schools in poor areas, makes perfect sense. Military-run institutions would turn out compliant citizens willing to take crappy work-experience placements without complaint, and never flinch when being bawled at by someone paid to pretend to be offended by their shelf-stacking technique.

The militarisation of the British psyche in recent years means TV viewers are more likely to envy the trainee officers on BBC4’s Sandhurst than pity them. The fashionable belief that the militarised consciousness is superhuman leads them to view the James Blunt clones kowtowing to their superiors as heroic, rather than deluded.

See more: military in society,